As I mentioned in my 5th International Wudang Taichi Tournament post, traditional martial arts are undergoing a period of change. Well, more accurately, they are constantly changing, not only from generation to generation or year to year, but from moment to moment. I will not try to define traditional martial arts, because to do so would be to limit and diminish them. But I can talk about the faces the art presents, the way it adapts to narrow niches in order to survive in the material world. Survival means that the narrow but popular and materially viable niche thrives and sustains the art so that a new generation can be trained in the deeper traditions.

From the stories our Master has told us, kungfu schools here in Wudang a few decades ago resembled nothing so much as street gangs. I speculate, but it seems the art was still reeling from a loss of relevance. Individuals were still trying to exist as they had when fighting was the daily test of the art. But in truth modern combat, in warfare and elsewhere, had no place for them. Still speculating, but I think the turf fighting between kungfu schools that our Master has spoken of was evidence of Wudang kungfu’s displacement. While a few individuals kept the spirit of the art, its true face was lost behind an outdated mask. Kungfu schools attracted few students and slowly dwindled away. After all, why send your child to a school if the only future it offers is violence and eventual imprisonment?

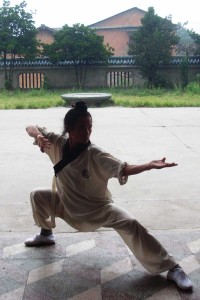

More recently, traditional kungfu has adapted by taking on new appearances. It caters to entertainment, tourism, sports, and health. Each of these outlets are, as I said of the Taichi tournament, narrow but necessary expressions of kungfu. Movies and TV keep the art alive in the popular imagination, though they twist the image so as to be more attractive. Performing for tourists and teaching them for a few days at a time brings in a little much-needed money, and wins the support of political and economic leaders who also profit from the tourists. Making a sport out of the art provides an publicly acceptable competitive outlet, the same thing the old street gang kungfu schools failed to do. Kungfu also appeals to those who search for a well-rounded health practice, though this too is only a small facet of the larger practice.

But if the art only exists in these outlets, it is lost. No one of them (or even all of them together) encompasses the breadth and depth of the traditional teachings. Nonetheless, we who want to preserve the old ways must accept both the necessity of these outlets and the responsibility of maintaining the integrity of our practice. And hope that someday the world will once again value this hidden treasure.