It’s been well over a month since my last post. Our training schedule has been in chaos for the last month, and it just seems like every time I might sit down and write, there is a competition, or a performance, or a meditation period, or a bad internet connection, or something else to get in the way. A change is as good as a holiday, though, and I feel refreshed and ready to go now that training in Wudangshan is settling back into normal routine.

The month of May and the beginning of June were fairly stressful, because it seemed like we were never going to get a real day off to recover from all the events mentioned above. Everyone in our class, I think, felt this tension building under the calm we are trying to maintain. The harder we tried to keep a lid on stress, the more rigid our emotions became, and that rigidity fanned the embers of the stress inside. The calm produced was not really calm at all, but a facade over inner turmoil. One has to somehow face stress while staying light and happy. This seems impossible; the two seem mutually exclusive. One feels one must either escape the stress or embrace unhappiness. But we can’t do either.

This balancing of seemingly mutually exclusive elements is a reoccurring theme in my training. From day one, coaches yell at us to sink our stances lower, but keep our backs straighter. This seems impossible. To keep balance, you feel that you have to stick out your butt and lean your head forward if you want to get your stance lower. Or the coach tells you to do the movements faster and clearer, but you are already going as fast as you can and you feel the only way to go any faster is to fudge the movements. But though you ask the coach again and again to choose one of the opposing criteria for you to focus on, he keeps you on both horns of the dilemma. And then one day, through long, hard work, low and straight becomes possible, and fast and clear becomes fierce.

Often in our decision making, and particularly in the processes by which we find our emotional response to stimuli, we are too lazy to seek an ideal answer. Instead, we try to determine which extreme reaction will give the best result most of the time. Psychology calls this heuristics, and it is a very real part of how the human brain works. These shortcuts save time and reduce the amount of thinking we really have to do, but they also oversimplify our inherently subtle world and thus make our path through it clumsy and misguided.

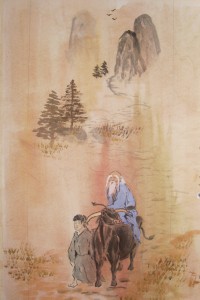

I think this is one reason meditation is so important: meditation changes the way one values time and helps prioritize balanced thinking instead of headlong speed. By slowing down and observing with greater sensitivity, we can hope to face each challenge with the right calm-happy, lazy-driven, optimistic-pessimistic, black-white, free-disciplined, push-pull, fast-clear, low-straight, give-take, yin-yang response.